Republished from: https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2024/05/15/it-s-a-scam.html

Securing cyber frontiers

Australians are losing more money to scams than ever before – more than $3 billion a year – in what appears to be a ‘golden age’ for scammers. Cybersecurity expert Dr Suranga Seneviratne is researching ways to outsmart them and to avoid data breaches. He believes scams are about to get more sophisticated, but envisions an increasingly ‘cybersafe’ future.

What scams are currently most common in Australia?

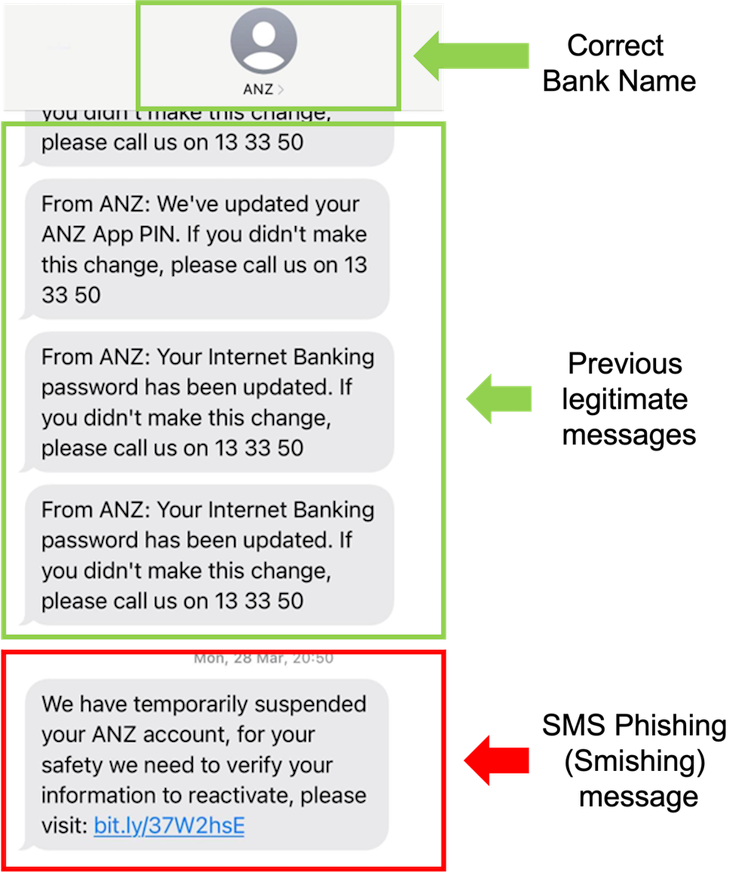

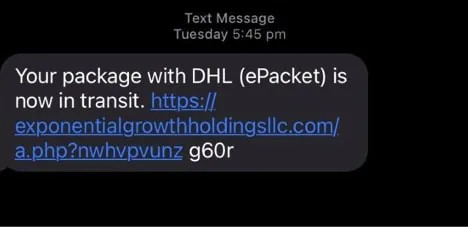

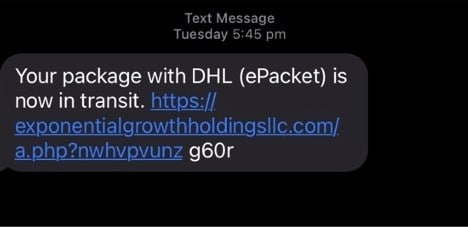

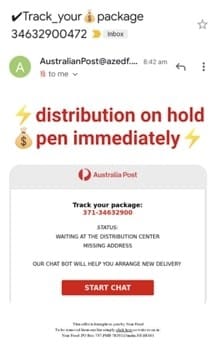

There is a universal pattern of what we call ‘spray and pray’ attacks. These are SMS messages or emails that are crafted in bulk and sent by attackers or organised crime syndicates to millions of people, hoping to catch at least some people. These messages are along the lines of “You missed this delivery” or “We noticed this unusual activity in your bank account”. Or around tax time, there might be messages related to problems with your tax return. Also common are Facebook Marketplace scams using PayID. That’s when the scammer, pretending to be a buyer, tries to convince the seller to accept payments via PayID. They then send a fake email which appears to be from the bank, asking for the payment of a fee to activate or increase the payment limit of PayID.

We’ve also noticed scams moving into other channels. Scams used to be sent via SMS and email – but now they’re increasingly being sent via social media and messenger apps. For example, on WhatsApp, there is this scam along the lines of, “Hey Mum, this is my new phone number, I lost my previous phone. Can you transfer some money?”

What are the key emerging cybersecurity threats?

The thing that keeps me up at night is the impact of generative artificial intelligence (AI) and how it could give scams a significant boost. It’s the automation and scaling up of scams that I’m most concerned about. Phishing and marketplace scams have previously involved human effort. Soon they might be fully automated, executed in good English and personalised to their targets. They’re likely to be using email samples and contextual information from social media posts to mimic the writing style of real people or organisations. Some will use convincing images and even AI-generated voices. All of this will create more persuasive, plausible messages that people tend to believe more.

A hacker used to target one or two businesses, but now they can use an AI-based tool to attack hundreds of businesses overnight. This will create scams on a scale that we haven’t anticipated, and we don’t yet know what impact this will have.

Who is most vulnerable to scams?

I’m most concerned about people who are already experiencing disadvantage – the elderly, immigrants, and people with language problems. They tend to fall victim to these messages because they’re not aware of the patterns and they’re also new to what’s happening in Australia. I can’t conclusively outline the numbers, but in my experience, I have seen more cases in these communities than any other.

Why do people fall for scams?

It’s more psychology than financial desperation. Scammers are highly skilled manipulators who use social engineering and emotional triggers. They take advantage of a lack of awareness or vigilance by people who are leading busy lives. There is often some sort of urgency in the matter, and we tend to want to act because we’re worried and want to respect authority. However, if you have heard about these typical patterns, then you’re more likely to figure out that it’s a scam. In the past, we have mostly tried to push this problem towards the users – the idea being that they fall victim to scams because they don’t know any better. But one thing we firmly believe is that the technological solutions must be also ready to assist them, so that these attempts don’t reach users in the first place – so that is something we are working on.

What research and practical measures are you working on to combat scams?

Cybersecurity has always been an arms race between attackers and researchers. As security researchers, we need to identify vulnerabilities and potential threats before they are exploited, and come up with countermeasures when attackers change their strategies.

Right now, at the University of Sydney, we’re developing AI algorithms to detect freshly launched phishing URLs (website links), in a project funded by the Defence Innovation Network, in collaboration with Thales Australia. Phishing is when attackers attempt to trick users into doing the wrong thing, like clicking a malicious link that will download malware, direct them to a dodgy website, or to a login screen impersonating a popular website.

While many existing solutions can detect phishing emails and SMS messages, attackers can evade them. So we’re working on a solution that analyses the URL information and draws on the capabilities of Large Language Models (AI learning models that are pre-trained on vast amounts of text data to generate new text content) to build better-performing phishing detectors.

We’re also building technologies that will enable companies to collaborate on training their AI models, without revealing their sensitive data. This will enable them to develop what’s called ‘cyberthreat intelligence’, by finding solutions together.

In addition, we’re working to raise awareness about scams in the media, and will be offering more education in the cybersecurity area in future. We need to be instrumental in brushing up people’s skills, for example through micro-credential courses, reaching audiences beyond university students. To deliver this education, we’re building a cyber training lab at the School of Computer Science that will open in early 2024.

How do you envisage the cybersecurity future – will the proliferation of scams ever subside?

I’m not going to say that we will completely outsmart the attackers, but in terms of our skillset as a nation, if we have enough awareness, technology and knowledge – and the workforce to address it – then we should be able to identify scams early. We should be able to get on top of things quickly when attacks happen and respond before they affect many people. Until then, we need to be more vigilant than ever.